When the React Server Components RCE (CVE-2025-55182) dropped, most teams did exactly what they should have done. They focused on understanding the exploit, shipped emergency detections, and worked to prevent the worst-case outcome.

That response was necessary. It also created a blind spot.

Once we started reviewing real traffic, it became clear that the most operationally important activity was not the RCE itself. It was the follow-on probing and exploitation of different bugs in the same surface area, using payloads that did not resemble the original exploit, despite sharing some common characteristics.

CVE-2025-55183 and CVE-2025-55184 are a good example of how this happens. They arrived close together, affected the same ecosystem, and were often mentally grouped with the RCE. In practice, they behaved differently enough that teams relying on “we already have RCE coverage” assumptions risked missing them entirely.

This write-up focuses on what mattered once traffic hit production: how these newer CVEs actually showed up, why binary detection logic struggled, and what this episode reinforces about building runtime defenses that hold up during disclosure week.

The important correction: these are not RCE variants

It is tempting to treat everything that follows a major disclosure as a variation of the original bug. For the React Server Components issues, that assumption does not hold.

CVE-2025-55182 and related variants revolve around unsafe deserialization and prototype pollution, often leading to dangerous server-side module access and, in the worst case, remote code execution.

CVE-2025-55183 and CVE-2025-55184 exploit different classes of bugs.

One focuses on source exposure via malformed Server Function arguments. The other targets denial of service through pathological argument coercion and deeply malformed input structures.

They share an ecosystem, not an exploit shape. Detection logic that assumes otherwise tends to overfit to the first disclosure and underperform on everything that follows.

What the new CVEs looked like on the wire

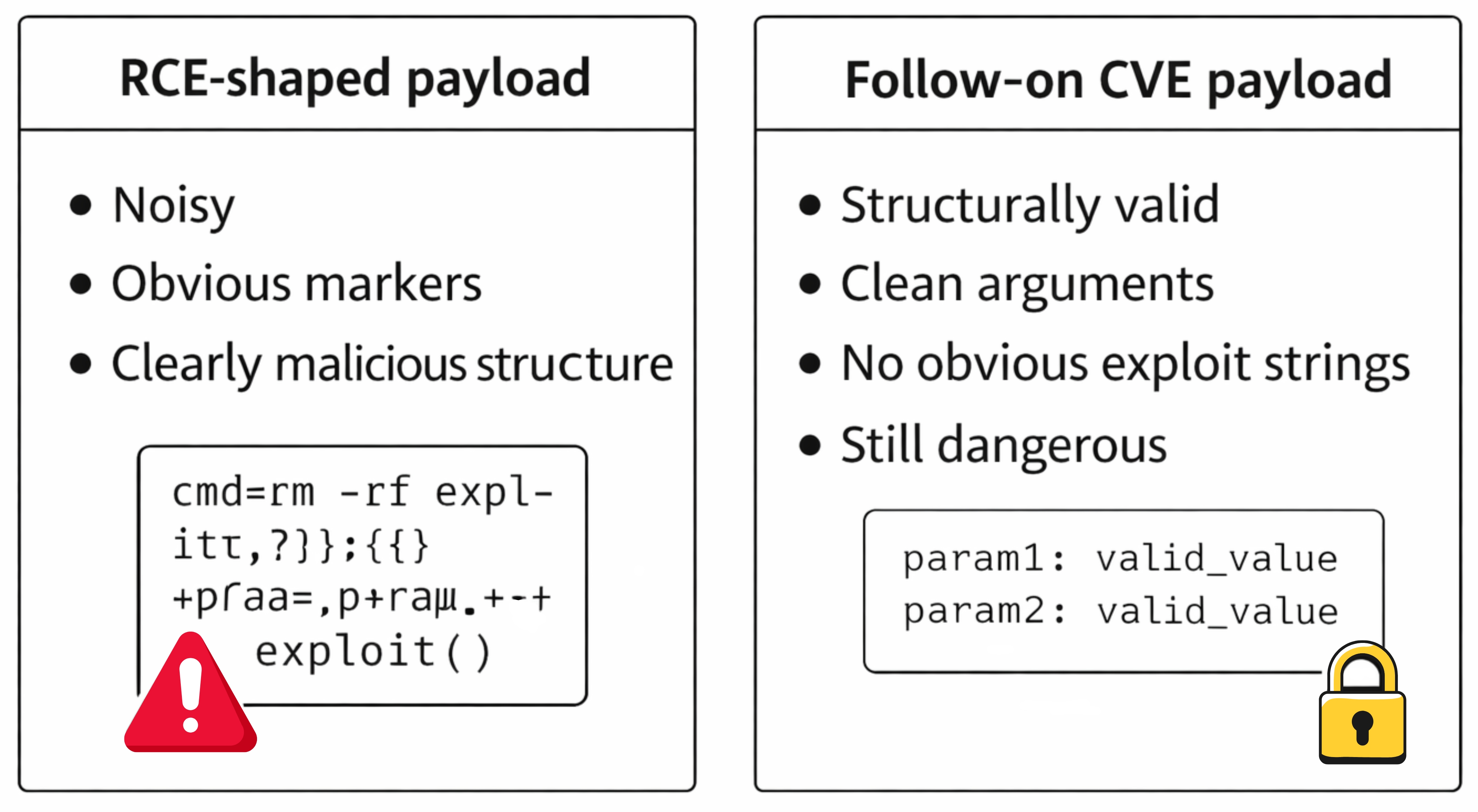

Early traffic for these follow-on CVEs was React-adjacent but not RCE-shaped.

Instead of the familiar indicators defenders had just trained themselves to look for, payloads showed patterns tied to Server Function invocation and argument handling behavior.

In practice, this meant requests that:

- Looked structurally similar to legitimate React traffic

- Lacked prototype pollution markers entirely

- Triggered edge-case parsing or coercion paths

- Sought to extract internal values rather than execute code

From a detection standpoint, these payloads were dangerous precisely because they were clean. They did not trip the alarms teams had just spent days refining.

This is often the point where teams believe they are protected because their primary RCE rule is firing, while a different class of exploit is already landing quietly.

Why early coverage was uneven, even with good RCE rules

Some teams did catch portions of CVE-2025-55183 and CVE-2025-55184 traffic early on. When that happened, it was usually incidental.

Coverage appeared when:

- Attackers combined techniques and reused prototype pollution primitives

- Payloads overlapped with existing scoring indicators

- Contextual protocol markers raised suspicion even without explicit exploit strings

Coverage disappeared when:

- The payload was a pure source exposure attempt

- The denial of service vector relied only on malformed nesting or coercion behavior

- The attacker intentionally avoided well-publicized RCE markers

This inconsistency is not a tooling failure. It is a modeling failure. The detection logic was correct for the first problem and incomplete for the second.

Why binary detection breaks down during disclosure week

Many runtime protection systems ultimately make a binary decision: block or allow.

That works when exploit patterns are stable. It works poorly when:

- Payloads are evolving daily

- Attackers are probing rather than exploiting

- New CVEs share surface area but not mechanics

Binary logic forces an early choice between over-blocking and under-seeing. Both outcomes are costly. One breaks production. The other removes your ability to learn.

The real loss is not just missed blocks. It is missed visibility.

A scoring model turns unknown variants into useful signals

A more resilient approach treats detection as a spectrum rather than a switch.

In practice, this means classifying traffic into at least three operational buckets:

- Likely reconnaissance or probing

- Suspicious but ambiguous

- High-confidence exploitation attempts

This matters because follow-on CVEs often share partial structure with known issues even when their exploit strings differ completely. Accumulating weak signals allows you to surface activity early without committing to aggressive enforcement.

Just as importantly, it gives you artifacts to analyze later. Being able to say “we saw this shape weeks ago” changes how incidents unfold internally.

What this means for your detection stack

If you are responsible for runtime detections, ingress controls, or API protection, a few concrete checks are worth making now:

- Validate your assumptions about related CVEs. If your coverage for CVE-2025-55182 is primarily signature-driven, ask whether CVE-2025-55183 or CVE-2025-55184 would generate any signal if they appeared as clean, standalone payloads. If the answer is no, that is a real gap.

- Look closely at what happens to low-confidence signals. If traffic that does not cross a block threshold is dropped or ignored, you are losing the earliest warning you are likely to get during disclosure windows.

- Separate logging decisions from blocking decisions. You should be able to log aggressively without taking on outage risk. If those two decisions are coupled, you are forcing yourself into unnecessary tradeoffs.

- Make sure payload retention and deduplication are in place. Most exploit traffic collapses into a small number of repetitive variants. The value is in the outliers. If you cannot answer what distinct shapes hit you in the first 48 hours, you are flying blind.

- Pressure-test detections against shape changes, not strings. Ask whether partial structural matches still surface suspicious behavior, or whether everything depends on exact markers staying stable.

None of this is about perfect coverage on day one. It is about preserving visibility while the ground is still moving.

Handling CVEs as a learning problem, not a rules problem

The broader lesson from this wave is procedural, not specific to React.

Teams that fared best treated the disclosure window as a data-gathering phase. They captured reconnaissance, saved payloads, clustered variants, and tightened logic based on what actually showed up, not just what advisories described.

That approach requires accepting uncertainty early and designing systems that degrade gracefully rather than fail silently.

It also requires resisting the urge to declare victory once the first rule ships.

Closing thoughts

CVE-2025-55182 deserved the attention it received. RCE is the most severe outcome. But CVE-2025-55183 and CVE-2025-55184 are reminders that attackers do not need RCE to cause real impact.

Source exposure and denial of service both lead to incidents. Both show up differently than the headline exploit. Both are easy to miss when defenses are tuned too narrowly to the first disclosure.

The takeaway for the security community is straightforward.

Optimize for visibility early. Treat reconnaissance as signal. Assume related CVEs will not look alike. And build detection systems that let you learn before you are forced to respond.

The exploit matters. The behavior around it tells the real story.

.svg)